Introducing the Practices by Hirosaki University Elementary, Junior high and Special Needs Schools

The Sound Project at the Junior High School

The Faculty of Education at Hirosaki University, where I teach, has four affiliated facilities: kindergarten, elementary school, junior high school, and the special needs school. Students who aim to become music teachers at junior high schools are required to engage in intensive internship training at the affiliated junior high schools in their third year. The following practical training is conducted five times a week during the spring and fall semesters for a total of 20 lessons (50 minutes per lesson). This program, called the Sound Project, was designed by me based on R. Murray Schafer’s Sound Education. They will have already experienced the sound project in my music education class during their sophomore year. This internship practice led by the university faculty is unique to Hirosaki University, and this program, based on Sound Education, has been developed over a period of about 15 years with the cooperation of the music teachers at the affiliated schools.

The sound project begins with a soundwalk, a walk in which the children listen to all the sounds around them while maintaining a space of solitude and not talking to anyone. The soundwalk requires a leader to design the course in advance. Third-year students investigate various sounds inside and outside the Hirosaki University Junior High School building in advance and come with a soundwalk that features interesting acoustic spaces and experiences. They take the lead in the actual musical performance as student teachers, leading the junior high school students while paying attention to, for example, the sound and feel of shoes hitting different kinds of ground, sounds coming and going from far away, sounds that can be visualized, and artificial sounds that occur suddenly, one after the other, sometimes mixing and diffusing. The sound environment in the open air is more dynamic than the students expect. With a good leader’s design and guidance, students can enjoy the soundwalk as if they are experiencing a composed work. Environmental sounds are, of course, fickle, so it is not always possible to hear the sounds you design in advance. Wind, birds, and people move at will. In such cases, the leader guides nature as if they are improvising. Since the actual soundscape is unstable, the leader (student teacher) also has to take on both roles, as composer and improviser.

On the afternoon of May 21, 2013, the most striking feature of the day was the sound of the wind. The junior high school students took time to create a physical connection with it. The wind would approach from afar, resonate with their bodies, stimulate their senses, and eventually drift away. At the same time, various types of wind formed a soundscape. After returning to their classrooms, the junior high school students verbalized these sounds. Their words were the result of their attempt to faithfully trace the sounds they heard. They tried to capture the unshakable acoustic information as a signifier without giving the sound any narrative meaning.

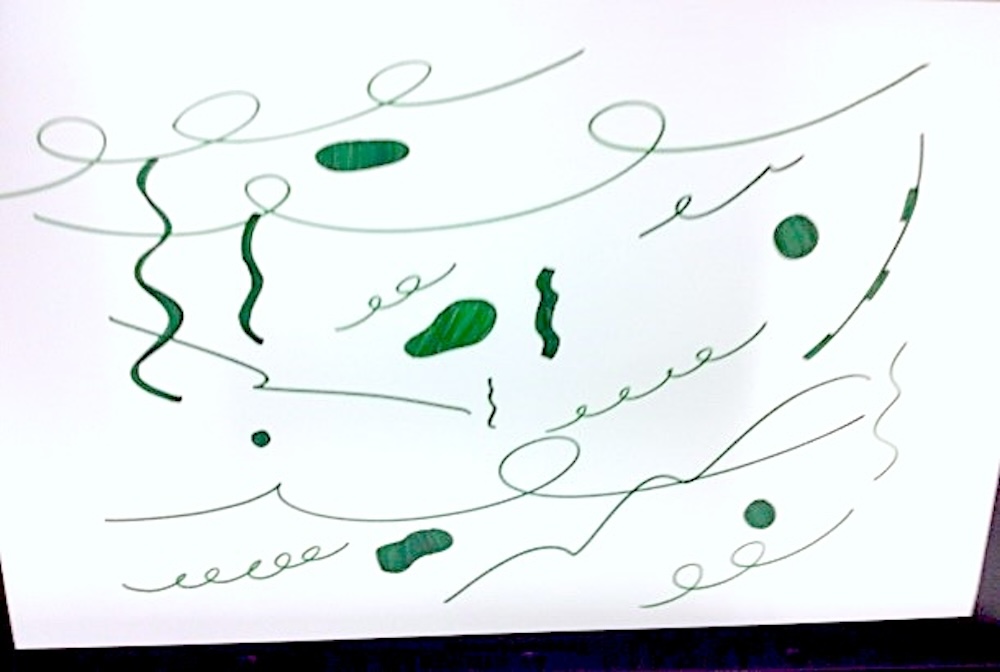

On the afternoon of October 31, 2017, a group of third-grade middle school students each found a favorite spot and listened to environmental sounds for three minutes at a fixed point. When they returned to the classroom, they traced their listening experiences in graphic notation rather than in words. This minimal activity led them to the next creative activity following the soundwalk. The experience of soundwalk, that is, the impression of the soundscape, can lead to an expression using, for example, graphic notation as a medium. When drawing a graphic notation, try to represent the experience of sound as much as possible in terms of shapes (i.e., do not make the experience of hearing a bird’s voice explicit with an illustration of a bird). In the performance of graphic notation, I asked the junior high school students to use graphic notation that is not created by themselves but by others, so that the work does not become a mere imitation of the sound environment. This is a way to let the students play with the work as a new kind of signifier, without binding the graphic notation as a story (signified) of their own experience. The work can be created by a group or an individual, but by using familiar materials as instruments and students’ own voices, the principles of universal design, flexibility, simple intuitiveness, and tolerance for error can be ensured.

A Joint Class between the Junior High School and the Special Need School

Yohei Koeda, a music teacher at the Hirosaki University Special Needs School, teaches students with pervasive development disorder; Down syndrome; autism and so on at the Hirosaki University Special Needs School. Regarding a tendency of music at special needs schools, Koeda points out that teachers often expect their students to explain music in words and practice to improve their technical skills. The students, in a sense, have to deny themselves of today in order to grow to manhood in the future. Thus, any music activities are expected to contribute to the students’ problem-solving, improving sociability, and acquiring adaptive capacity. As a result, the disabled students have to deny their own identities first, and then, attempt to improve their disabilities in order to get closer to so-called non-disabled, even though in music classrooms. These classes easily develop such dichotomy as adult/ child, teacher/ student and disabled/ non-disabled and so on. What is more problematic, however, is that these dichotomies above can be considered as binomial oppositions based on the relationship between superiority and inferiority. In order to transfer the process of self-denial to the process of self-affirmation, Koeda brought his students into the soundwalk. His students used to be instructed how to sing for audience in school ceremonies and events. These songs for them were, however, very much simplified comparing to songs for regular junior high school students usually sing. According to Koeda, his students were somehow aware of their “musical” ability, gave up to sing like those non-disabled students achieved and eventually internalized their own helplessness. The soundwalk, however, gave them an opportunity to open their ears to soundscape, to listen beyond those school songs. They found their own footsteps on manhole lids, plastic bags swayed by wind far away and then concentrated on listening to a profound silence. After the soundwalk, they undertook an instrumental improvisation based on their soundwalk experience. This session was held on July 2017. Each student picked up their favorite instruments such as the xylophone, the Cajon, the tambourine, the ukulele, the drum, the koto and so on. This is because some students had extreme directivity for a particular sound. In order to enable students to create their own sounds, some hand signs and gestures were instructed by Koeda (he referred to the Japanese composer and multi-instrumentalist Yoshihide Otomo’s method). The students along with their own instruments made a big circle and a leader (conductor) designed by computer application went the center of the circle to give them hand signs for their own instrumental improvisation. Those simple and intuitive movements and sounds created by the students gradually swept away the dichotomy between disabled and non-disabled.

This was actually verified in the next session: a joint class with a junior high school. On October, 2018, a joint class with special need schools was taken place at Hirosaki University Junior High School, instructed by Koeda and Motoko Saito (music teacher at the Hirosaki University Junior High School). Tomoe Iwabuchi, the head teacher at the junior high school at that time, also played a pivotal coordinating role for the joint classes between the two schools. Both special need and junior high school students picked up their favorite instruments such as the hand-bell, the guiro, the shaker and so on. Once again, the students along with their own instruments made a big circle and a leader (conductor) designated by computer application went the center of the circle to give them hand signs for their own instrumental improvisation. The session was quite successful since they had already learned how to listen, move their bodies and response to others through the previous excises. What should be noted is that the junior high school students learned most from the special needs students in terms of musical flexibility and creativity.

In a music class using regular materials that are simplified and trivialised versions of Western classical music, it would be almost impossible for children with special needs to take the initiative, but in this class, these physicalities surpassed those of the children at the attached junior high school. Most importantly, the junior high school students recognised this fact and found musicality and artistry in the movements of the children with special needs. This is why, in a post-class questionnaire, one student commented, “At first I didn’t know how to move, but after watching the movements of the special-needs students, I gradually began to understand. “

Practicing Soundwalk and Graphic Score at the Elementary School and the Junior High School

At the elementary school (first-year class by Rumiko Kamiyama and fourth-year class by Asami Kimura, July 2018) and the junior high school (first-year class by Imada, May 2018), a performance of a graphic score created from the soundwalk experience was conducted using voices (the elementary school) and instruments (piano and cello, the junior high school). The students were asked to create their own musical score. In the process of creating the piece, differences were observed between groups that selected the notes they wanted to use and the method of reading music (junior high school) and groups that interpreted the waveforms, overlaps and blank spaces in the graphic score and voiced the shapes as they were (the elementary school). One of the junior high school students commented on her own performance: “Gradually, the shapes and lines increase and the white parts decrease. White gives me an image of nothingness, so I thought that the nothingness was decreasing, which meant that the sound was increasing.” The children themselves were involved in the interpretation of the graphic score. The fact that the children themselves collaborated in interpreting the graphic score, the fact that they used modern music techniques such as internal string and percussion techniques and a prepared piano instead of conventional piano techniques, and the fact that they themselves were responsible for all aspects of music creation, suggest that both the concepts of sound education and universal design functioned effectively in this practice.

Let’s Find Existing Sounds and Create a New Soundscape

Since 2017, Hirosaki University elementary and junior high and special needs schools have also explored music education practices using ICT devices, taking the opportunity of the new coronavirus pandemic and the GIGA school concept to continue joint research in music education. The following are practices A and B for 77 students in 2021 (26 in the second grade of elementary school, 33 in the third year of junior high school, and 18 of the affiliated special needs school in the junior high school). We call the following series of practices “let’s find existing sounds and create a new soundscape.”

Practice A: (1) Exchange through “sound cards”

(1) Discover sounds through sound walks around each school. (2) Create QR codes that record favorite sounds using applications. (3) Create and exchange of “sound cards” between schools, using QR codes to write one’s name and favorite sound, etc. (4) Play and listen to the QR codes of the “sound business cards” at each school.

Practice B: Exchange through “sound collage”

(1) Collect “water sounds,” “footsteps,” and “favorite sounds” using applications at each school and create QR code label stickers with the recorded sounds. (2) Exchange label stickers printed with each QR code in the gymnasium of the attached elementary school. (3) Have mixed groups of elementary, junior high, and special needs students paste QR codes on the walls and floor of the gymnasium (done while playing and checking sounds). (4) Improvising by playing QR codes in groups and as a whole.

A descriptive questionnaire was sent to participating students after the event, who made the following comments:

Elementary school student A: When everyone played different notes, it was like playing, and the beautiful sounds became like a melody. Sound is beautiful.

Special needs student A: I enjoyed looking for interesting and beautiful sounds. I learned a lot from listening to people in elementary school and at school, and from searching for sounds. I enjoyed my class today I would like to play with everyone again.

Junior High School Student A: When I listened carefully to various sounds before this class and during the preparation stage, I realized that there were many sounds in this world. I am sure I will encounter various sounds in my life, but I think that I would like to live my life by being exposed to them.

Junior High School Student B: Until now, I have not thought deeply about sounds. However, this study allowed me to think about sound face to face. It was interesting to learn that different people who recorded sounds could make differences even with similar sounds.

Koeda noted comments such as an increased awareness of the need to listen carefully to sounds in daily life and an awareness of individual differences in sound preferences and approaches to materials. He concluded that the music teachers had learned enough from activities in which diverse children learned from each other, using sounds as a starting point for interaction.

(Tadahiko Imada)

Remark: This article is excerpted and compounded from the following papers:

Imada, T, Tsukahara, K, Chiba, S and Koeda, Y. (2023). “Music education and social inclusion: Resolving the dichotomy between aesthetics and ethics.” Music in the Life, Life in the Music: The 14th Asia-Pacific Symposium for Music Education Research Conference Proceedings. 284-292

Imada, T. (2023). “A Sheet of Paper Considered an Instrument.” The Routledge Companion to Teaching Music Composition in Schools. pp.206-221 DOI:10.4324/9781003184317-19

Imada, T, Tsukahara, K, Chiba, S and Koeda, Y. (2021). “Exploring the Inclusion and Equity in Music Education.” Exploring Possibilities and Alternatives in a Changing Future: Proceedings of the 13th Asia-Pacific Symposium for Music Education Research. pp.321-327